So what does effective leadership of primary history look like?

A case study

When Lara took over as history subject leader 3 years ago this was her first whole-school role. She volunteered to be leader of history as she had enjoyed her A level studies but felt daunted and more than a little overwhelmed about influencing other more experienced and competent teachers’ practice.

Lara took time to develop her leadership of the subject, feeling her way into the role by looking closely at all year team’s schemes of work as a paper exercise, supported by attending year teams’ planning meetings when history was in focus, as well as some team teaching in some year groups she had never taught.

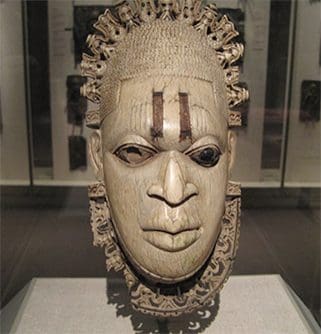

What she quickly found was a surprising range of practice, even with some tight planning and strong teaching. What was missing was a sense of what it meant to teach history and not just finding out about the past. Added to this, teachers were trying to cover too much content: fun but not helping pupils to develop their capacity to thinking historically. Quickly Lara saw the need to build a clear understanding of what it meant to ‘get better at history’ and was able to develop some common principles which were sufficiently clear for all staff to embed them in their teaching throughout the school.

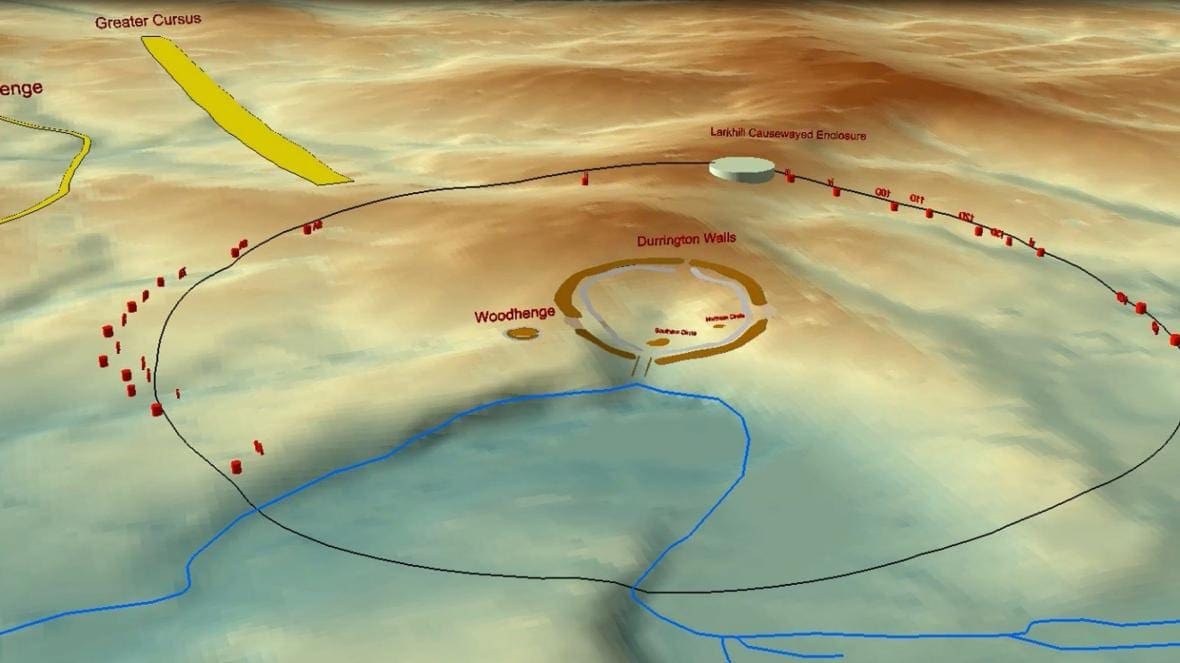

One of the breakthrough moments was when Lara converted staff to adopting a more enquiry-based approach. Realising that staff felt there was already so much to do in in history, she distilled every topic down into just 6 enquiry questions, no more. Now staff felt that this was manageable for the first time. She then ensured that each question related tightly to an important historical concept (cause, change, interpretations etc) not just ‘what was X like in the past’. By framing the enquiry questions in such a way that the historical concept was central, she ensured that no-one could avoid teaching it and could not retreat to just building up factual knowledge. During any drop-in session Lara would simply pose the enquiry question being discussed and see how well the pupils were able to answer it.

From this position she then felt able to see progression more clearly across the key stage. How was looking at cause and consequences, for example, in Y3 made more challenging in Y5? She found this hard but central to her work if standards were to rise. Quickly she found that expectations became higher as Y5 staff could see that they’ve done this sort of work in Y3. They now needed to add new dimensions not just different content.

The second breakthrough moment came next. Having sorted out the enquiry questions and which concepts were going to be prioritised in each topic she then took the bold step of insisting on at least one formal common assessment task for each topic. Each had a different focus. By providing a markscheme for each task she was able to set clear expectations of the standard hoped for. Instead of feeling intimidated by yet more assessment, colleagues actually looked forward to looking at the pupils’ work. Because they knew exactly what they were teaching and were spared covering too much content, they genuinely wanted to know if what they had taught had been learnt! Confidence grew. Then standards improved, year on year as staff could see which learning activities promoted better outcomes.

The work in history has now been used as a model of good practice for other foundation subject leaders to follow and will provide a driver for overall school improvement in the future.

Lara admits that she was very lucky in that she work with a fantastic staff who are all willing to get on board with the changes because they could see the results. They felt they were better teachers doing the right things at last. We all want that!