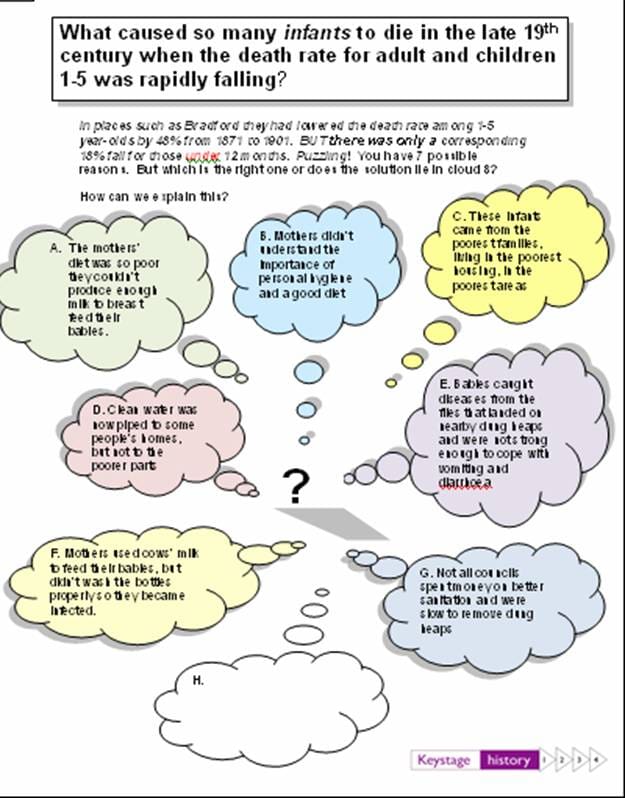

It came as no surprise to read in OFSTED’s report ‘History in the Balance’ that the ‘key element’ of interpretations was still relatively badly taught. Having been a central part of the history National Curriculum (and to my mind the jewel in the crown) for 25 years now, you would have thought that departments would have got it licked. Its inclusion has survived every curriculum revision from 1995 to 2000 to 2014. Rather than repeat what has been said very well in other places, particularly lucidly by Tony McAleavy in 1993, I will offer you some practical advice and point you to examples of best practice.

So what is the problem?

In a nutshell, too many teachers still mistakenly call the differences in viewpoints of people living at the time being studied, interpretations. They are not. Interpretations MUST be the conscious reconstruction of an event etc after it has happened.