The downloadable six page document on answering source-based GCSE questions: matching learning strategies to question type, summarises the best advice from the examination boards all in one place. It gives you the sort of hints you should be passing on to your history students, from the words of the Chief Examiners. More usefully, it gives you strategies you need to help students with the aspects they find most difficult. Every type of source question is analysed in turn.

The key message that emerges relates to the way students engage with sources. Normally they see them as a whole, often with a caption underneath provided by the textbook. My radical approach is three-fold.

Firstly, strip each source of its anchoring meaning and of its provenance, and then ask students to think WHO would have produced it, WHEN and WHY.

Secondly, you could start with the provenance, without the source itself, and ask students to predict what it will say.

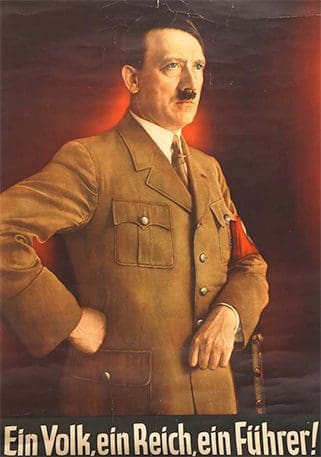

Thirdly, you could slowly reveal or drip–feed PARTS of the source, so the students have separate activities on parts of the source and then on the whole source. Making this distinction dignifies the importance of each. The more students rehearse this two-pronged approach the more likely they are to repeat it reliably in the examination. Many lessons on the site use the slow reveal technique, whether it is a starter for an SHP American West lesson showing contradictory paintings of Mountain Men or Modern World election poster from Weimar Germany.

The Outstanding Lessons on the site which exemplify these approaches are identified so that you can see how they work in practice and try out some of the ideas for yourself.

To give you a flavour of the longer document here are just 5 of the 20 or so ideas to whet your appetite.

1. Anonymous author.

Here you give students all the information they need about the source EXCEPT the author. Based on what the source contains, its tone etc, who do students think might have produced it? This speculation is important but there is no expectation that they will name them. You just want to find out if they are thinking along the right lines. Have they picked up the message of the source? Now it’ s time to introduce the author. The first question here is to ask SO WHAT?! In other words what difference does it make now that we know who wrote it? What else do we need to know about them?

What was their background?

What access to information did they have?

Do we know anything about their views and attitudes to the subject?

Does it seem as if the author is trying to excuse, mislead, show off, persuade?

Having determined the authorship can students work out the motive of the author. Here I play Who Wants to be a Millionaire? Which of the 4 possible motives seems most likely in the circumstances. I place students in teams to make it more competitive, but also to encourage them to think deeply about which of the 4 plausible motivations seems most likely.

2. With / without knowledge

Students are given a source, but the important contextual knowledge they need is deliberately withheld. Students realise that they can only go so far with their answer; they need more context. But rather than simply supplying it, encourage students to ask their own questions to clarify the essential context.

3. Ripples of certainty

Students are given a source in the middle of a large A3 sheet on which have been printed 3 concentric circles. In the inner most circle students write what they are sure about concerning the source. In the outermost circle they place their most tentative provisional ideas, leading on to discussion. This particularly helps students who are prone to rushing in and jumping to conclusions.

4. What a difference a date makes!

Students analyse a cartoon, for example of the Lytton enquiry over Manchuria, but are not shown the date. When the date is disclosed, students are asked to re-analyse. Does the meaning change? In this case the sarcastic comments made by the cartoonist about the tardiness of the League’s reaction only make sense when the students realise the interval between the event and the cartoonist’s reaction to the long-overdue report.

5. Date the source.

If we feel that students don’t use the date of the source sufficiently in their answers why not give them practice at working out the date for a cartoon or painting. The best example on the site probably comes from the History of Medicine. Can the students work out the date of the surgical operation from the internal clues. They are then told that it was a commissioned portrait whose purpose was to show the eminent surgeon at the height of his powers, confident but also up-to-date.

Often the all-important additional detail about provenance can be elicited from you in role as the painter or cartoonist. You do your research, using Google search or Spartacus site, and come in role. You only release information to the students in response to their good historical questions. The odd prop and dodgy accent helps make it fun!

A range of other strategies is included in the accompanying document. You will see them aligned with the type of examination question they help students to answer. We can all think of fun new ideas. The acid test is whether they deepen students’ understanding and increase their likelihood of answering appropriately in the exam. The methods shown have been proved to work.