In a recent article in the Historical Association’s Primary History publication the ever-reliable Tim Lomas attempted to identify the top 10 key messages to bear in mind when teaching the tricky concept of interpretations, before going on to explore the reasons why young children find it difficult. I want to put a gloss on Tim’s ideas but am keen to go further, offering more practical solutions cross referenced to actual lessons so you can see immediately how an idea has been successfully introduced in an all-important context.

Where Tim’s words have been reproduced they appear in bold, with my commentary in italics.

1. There is no one version of the past – we can tell different stories about the same event, person or situation

This can start as early as YR with pupils exploring alternative pictorial representations of familiar nursery rhymes or tales from the past.

2. Even if we could get close to the truth, different people in different places and times may consider differently which parts were important and why. Interpretations can change over time.

This is hard and should be reserved for the end of KS2. The Black and British unit we have written for Y6 shows how attitudes to empire and race have changed significantly recently.

3. The moment one tries to study history, you are immediately into interpretations. This is because no one can reconstruct everything that ever happened in the past and the very act of selecting involves a decision and hence an interpretation.

Often teachers fake an incident in the classroom with a colleague coming in an and reporting an incident that has just happened. KS1 pupils can all have a go at trying to reconstruct what was actually said-Its not easy. Imagine how hard it must be the to reconstruct the past, especially from a long time ago.

4. The past can never be fully recovered, so we have to be clever to make the best job we can of discovering it. It means that we often disagree about something in history but this does not mean that somebody is wrong and the other right.

OFSTED makes clear that they want pupils to go beyond simply creating alternative versions to working out why they might differ. So activities that involve selection and weighting are invaluable. If you were summing up a historic person’s achievements in a limited number of words would we all include the same things in the same order of importance. I doubt it. Many activities ask pupils to do this self-same activity and then the really important bit, go on to see how historians have tackled the task.

5. We can all have a good go at recovering the past. The main role is carried out by historians, archaeologists and museum curators but also by people such as journalists and economists – anyone who wants to use the past in their work.

On the site the focus is often on people with whom they can identify. Thats why we use curator’s dilemma as this Y6 example shows.

6. That does not mean that it is a free- for-all where anyone can just imagine the past as they like. A proper interpretation means following certain rules and using skills based on the evidence the pupils have.

This means pupils have to see it in action. The lesson on Alfed the Great shows this

7. Whilst all interpretations need to be looked at carefully and often respected, this does not mean that all history produced is equally valid. Some historical information is largely agreed and largely uncontroversial whereas other bits are clearly opinions or poorly rooted in useful evidence.

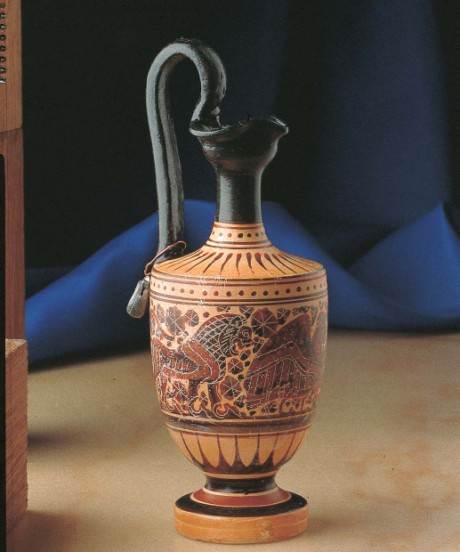

The sources on which the interpretation is based go a long way in allowing judgements on the validity of an interpretation.

This means of course that pupils have to find evidence to substantiate their conclusions. A good example of this is…

8. Interpretations can come in many different ways

– written versions such as historians’ accounts, archaeological reports, lectures, articles, textbooks; websites, podcasts, blogs, speeches, pictures, advertisements, film, radio, displays, historical sites, reconstructions, drama, historical novels, poems, music, myths, legends, comedy, theme parks, souvenirs, statues and monuments, games, graphs and tables, stamps and coins. They can be created by individuals, groups or societies.

Nobody is suggesting that you use all, or even most, of them. Just make sure you use some. Websites e.g. the BBC one on evacuation works well for pupils to actually critique, thereby showing that they appreciate that interpretations are there to be challenged as long as sound evidence is deployed.

9. Interpretations are not just about seeing whether something is accurate. It is possible to have something that is precise and accurate but can still be seen as distorted. It is worthwhile for children to considering what influences our own judgements and interpretations, such as the sources we use, the methods we use, our beliefs, values, nationality, background, personality, temperament, and influences such as patronage.

This works best of pupils have to create an interpretation from one particular groups point of view and then see how another, with a different perspective approaches things very differently, in terms of sources used, angles explored and conclusions draw.

10. An important part of looking at interpretations is to try to fathom out why they were created. They are invariably created for a reason – to support one side, to correct something that could be seen as distorted or imbalanced, to create new knowledge and ideas, to persuade, entertain, educate, preserve or commemorate

Once again a great example is the way government posters on evacuation create a very one-sided viewpoint