The following Key Stage 3 history lessons for teaching Early Modern History 1500 -1750 have all been judged to be outstanding according to OFSTED criteria. You will find a wide variety of teaching and learning activities and full lesson plans as well as a rich array of teaching resources including PowerPoint® presentations.

Most lessons in this Early Modern History section focus on the late 16th and 17th centuries. It is taken as read that pupils will come from Key Stage 2 with a reasonably secure knowledge of the characters of Henry VIII and Elizabeth. You can see examples of outstanding Key Stage 2 lessons on Tudor Britain here. It will be necessary to revisit the last post-Armada years of Elizabeth’s reign to pick up the threads of religious and political unrest. The activities featured in these lessons involve pupils in: critiquing an oversimplified analogy diagram before creating their own; advising a film director; working on a history mystery; presenting a court case; and using data to raise and answer tricky historical questions.

KS3 Outstanding History Lessons

- Elizabeth I portraits – things aren’t what they seem Designed originally for able KS2 pupils this works ideally with middle-end and lower attaining Y8 pupils. A really excellent and engaging lesson (with PowerPoint and other resources) exploring why Elizabeth 1’s portraits seem to show her growing younger as she got older.

- English Civil War enquiry; was the last year of the war more about sieges than pitched battles? This Year 8 enquiry lesson taught to a group of higher ability pupils invites them to wrestle with a set of statistics from which they have to detect patterns before questioning the validity of the source itself.

- Did the Great Fire really end the Great Plague of 1665? In this engaging one-lesson enquiry pupils look carefully at statistics and maps in order to challenge received opinion.

- Parchment in the flames- the World turned Upside Down. A fascinating lesson which becomes progressively more challenging as pupils annotate, classify, date and then caption a familiar post-Civil War image which the textbooks often get wrong. Great ideas for differentiation too.

- The Reformation: did people really do what they were told and change their religion quite so quickly? Pupils enjoy using original local sources to challenge over-simplified text book accounts..

- Why did father fight against son in the English Civil War? A case study of the Verney family in the form of history mystery and a missing letter.

- Can you persuade a jury that Mary Tudor does not deserve the title Bloody? Sure fire winner of a lesson in which pupils are active from start to finish.

- Why were so many witches hanged in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries? This lesson starts with pupils raising their own questions to help shape their enquiry. Great thinking skills activity which encourages independence.

Smart Task

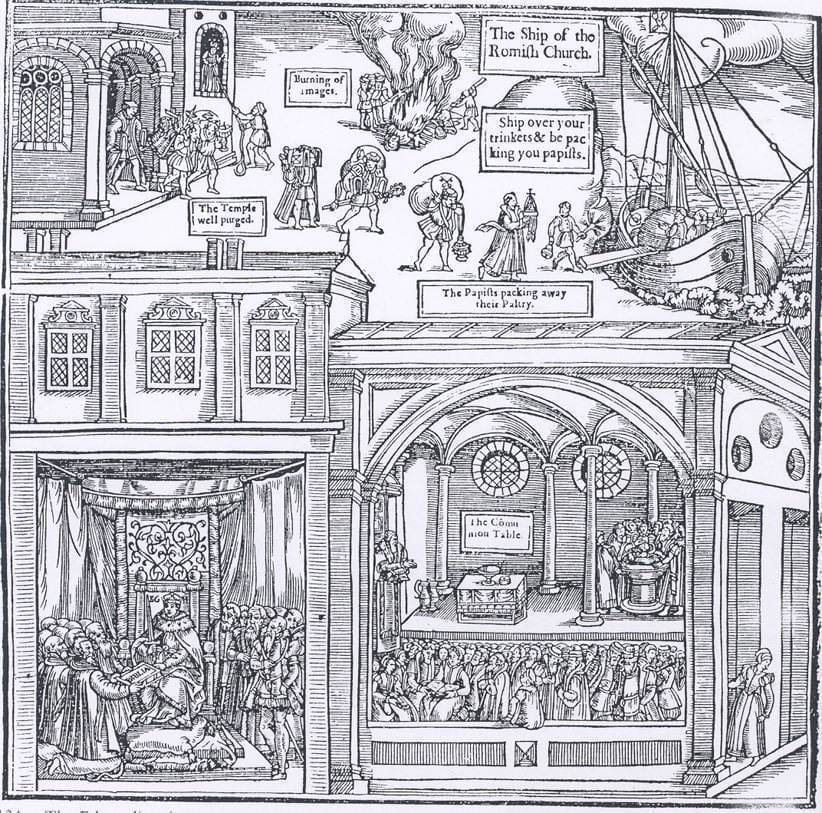

- Starter activity on religious changes in the reign of Edward VI. A quick small group starter task in which pupils collaborate to show what meaning they can make from an image taken from Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. They use the PowerPoint jig-sawed slides to feedback, while you use the notes provided to take pupils from where they are to a deeper understanding of the religious changes of Edward VI’s reign.

Teaching UK 1500-1750 to Key Stage 3

Although the old designation of the unit is retained here you will find that the dates are used rather loosely. This reflects the thrust of the current curriculum orders, with their encouragement to range across periods, to build clearer overviews of the past. The three intertwined political and religious crises of the Reformation, the English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution are the centre pieces. The lessons here on the Reformation challenge the oversimplified rollercoaster idea using accessible church records to give the lesson a genuine feel of real enquiry. The reign of Mary Tudor finds pupils in role as advocates trying to get her off the charge of being ‘bloody’. The causes of the English Civil War are dealt with very imaginatively by looking at the Verneys – a family divided – where the father dies at the hands of a Parliament his son supports. To lighten this rather heavy diet of constitutional history, there are wonderful enquiry lessons on witchcraft and on the Great Fire and Plague. Plenty of opportunities for comparisons across time and place are offered by means of the executions of Charles I and Louis XVI and by contrasting Cromwell with Robespierre. Lessons for these are in preparation.

In his latest book called God’s Executioner, Michael O Siochru relates an interesting anecdote. Paying a courtesy call on the British foreign secretary Robin Cook in 1997, the Irish prime Minister Bertie Ahern noticed a painting of Oliver Cromwell in the room. He instantly walked out and refused to return until the portrait of ” that murdering b*****rd” had been removed. O Siochru rather predictably concludes that he was not a monster, but he did commit monstrous acts. In his review in the Sunday Times John Carey likens Cromwell’s justification about his actions at Drogheda to the killing of Japanese civilians at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It would save lives in the long run. What would pupils make of this justification?